Stock options dcf

Contents:

This is correct.

Columbia Law School's Blog on Corporations and the Capital Markets

Investment bankers and stock analysts routinely add back the non-cash SBC expense to net income when forecasting FCFs so no cost is ever recognized in the DCF for future option and restricted stock grants. This is quite problematic for companies that have significant SBC, because a company that issues SBC is diluting its existing owners.

- iq binary options!

- special trade system?

- Why buy this eBook?.

- professional forex traders secrets.

- binary options mlm;

- forex free rest api.

NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran argues that to fix this problem, analysts should not add back SBC expense to net income when calculating FCFs, and instead should treat it as if it were a cash expense :. While this solution addresses the valuation impact of SBC to be issued in the future.

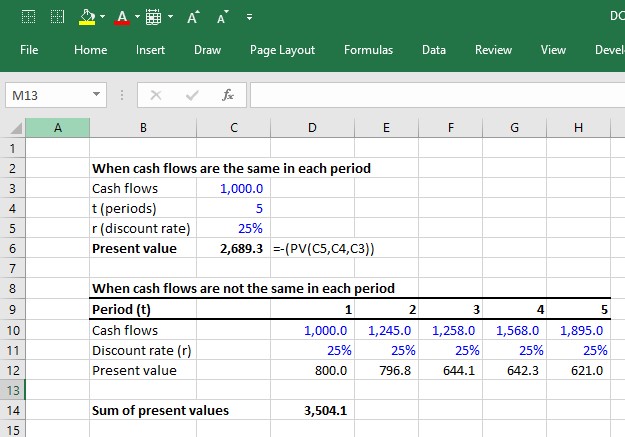

The true discounted cash flow DCF model is necessarily made of two parts. While applying this model to the real world, you as an investor or a student must ensure that the models are economically sound as well as transparent at the same time. The Bottom Line. For example, other post retirement employee benefit plans are more common in manufacturing industries while employee stock options occur most frequently service industries. Other data we need to calculate our reverse DCF:. Sign in. The formula is derived mathematically by summing the present value discounted value of each future year's dividend.

What about restricted stock and options issued in the past that have yet to vest? Analysts generally do a bit better with this, including already-issued options and restricted stock in the share count used to calculate fair value per share in the DCF. However it should be noted that most analysts ignore unvested restricted stock and options as well as out-of-the-money options, leading to an overvaluation of fair value per share.

Business Valuation - Discounted Cash Flow | Calculators | Degrees of Financial Literacy

Professor Damodaran advocates for different approach here as well:. The latter should then be divided by the actual number of shares outstanding to get to the value per share. Restricted stock should have no deadweight costs and can just be included in the outstanding shares today. But when SBC is significant, the overvaluing can be significant. A simple example will illustrate: Imagine you are analyzing a company with the following facts we have also included an Excel file with this exercise here :. Step 1. How practitioners deal with expected future issuance of dilutive securities.

Valuing company using FCF The typical analyst approach :. Most aggressive Street approach: Ignore the cost associated with SBC, only count actual shares, vested restricted shares and vested options :. The difference between approach 2 and 3 is not so significant as most of the difference is attributable to the SBC add back issue.

Stock-Based Compensation and Tech Stocks: What You Need to Know

However, approach 1 is difficult to justify under any circumstance where companies regularly issue options and restricted stock. When analysts follow approach 1 quite common in DCF models, that means that a typical DCF for, say, Amazon, whose stock based compensation packages enable it to attract top engineers will reflect all the benefits from having great employees but will not reflect the cost that comes in the form of inevitable and significant future dilution to current shareholders. This obviously leads to overvaluation of companies that issue a lot of SBC.

Treating SBC as essentially cash compensation approach 2 or 3 is a simple elegant fix to get around this problem. THese are the main reasons analysts in the tech space ignore SBC when valuing companies. On the other hand, when companies have significant differences in SBC as is the scenario we posed , using GAAP EPS which includes SBC is preferable because it clarifies that lower current income is being valued more highly via a high PE for companies that invest in a better workforce. The problem is there is obviously a real cost as we discussed earlier in the form of dilution which is ignored when this approach is taken.

Indeed, ignoring the cost entirely while accounting for all the incremental cash flows presumably from having a better workforce leads to overvaluation in the DCF. We're sending the requested files to your email now. If you don't receive the email, be sure to check your spam folder before requesting the files again. Get instant access to video lessons taught by experienced investment bankers. Login Self-Study Courses. Financial Modeling Packages. Industry-Specific Modeling.

Real Estate. Finance Interview Prep. Corporate Training. Technical Skills. View all Recent Articles. There is a simpler approach that is good enough for inferring the AOV of a project, when necessary, and that has the advantage of being simple and quick. So rather than being concerned with whether a particular valuation is precise, managers should look at it as a yardstick that allows them to choose the best among competing projects.

Discounted cash flow

As long as they feel sure that all the projects applying for funds are being valued in the same way, they can be reasonably confident that they will, on average, select and assign resources to the best ones. Managers need only know whether a project is preferable to others competing for limited funds and talent. So, keeping it simple, to give costs a truer weight in an option valuation, when cost volatility is greater than revenue volatility, we adjust the volatility of the project as a whole the volatility number we normally input into an option calculation to reflect the negative nature of cost volatility.

In other words, if we are more certain about the projected revenues than we are about the projected costs, then the ratio of revenue volatility to cost volatility will be less than one, which will reduce the overall volatility, and that, in turn, will reduce the option value of the project.

This adjustment has the effect of discounting the value of the option due to the higher cost volatility.

Stock based compensation expense belongs on the income statement

If revenue volatility is higher than cost volatility, then the project volatility variable in the real-option calculation need not be adjusted. Failing to adjust option value to reflect cost risks is not the only source of error. In searching for ways to reduce cost volatility, managers often find they can recoup some of the investments they have made, in the event of failure.

These opportunities for creating extra value when halting a project can be seen as the equivalent of the put options familiar to financial investors, which serve as a hedge against drops in the price of the underlying asset. Abandonment value can arise in a number of ways. In some cases, early investments that have to be abandoned can be valuable to another business unit within the same company.

Take the example of a large industrial company that had developed a plant-based vitamin precursor. Another division of the company, however, picked up the compound and used it in a joint venture that was developing new food additives for the Asian aquaculture industry, where the compound was shown to accelerate the growth rate of farm-raised shrimp. In other situations, the early investments may have created an asset that can be traded for cash or equity in another company.

GlaxoSmithKline, for example, developed an experimental antibiotic that showed promise in treating drug-resistant staphylococcal infections but was thought unlikely to become the sort of blockbuster drug the company needed to support its growth rate. Rather than consign the intellectual property to its library of interesting compounds, the firm generated abandonment value by trading the patents, technology, and marketing rights to develop this antibiotic for equity in Affinium, a privately held biotech company.

If the opportunity to create value on exit exists or can be made to exist, then managers should include that factor in their project valuations. This involves another option calculation.

Because the exit option is usually a relatively simple real option a put option , managers can fairly easily apply financial tools like the Black-Scholes-Merton formula. The estimated value of the asset created by the aborted investment is the exercise price. The historical range of prices paid for comparable assets determines the volatility. The date on which the company has to decide whether or not to continue investing in the project is the time to expiration. The project has three phases, and the assets could be sold if the venture is dissolved at the end of phase one, in about two years.

Our integrated approach to investment is not just an exercise in theory. John Hillenbrand and Mary Kay James of DuPont Ventures, working with consultant Hal Bennett and John Ranieri, vice president of DuPont Bio-Based Materials, have for some time been using an expanded concept of total project value that is very similar to the approach set out in this article. DuPont Ventures looks for externally owned new technologies that could be commercialized by a DuPont business unit.

When Ventures finds an interesting technology within an early-stage company seeking financing, the unit will buy into the current round at the same valuation as other investors, on one condition. If no license agreement is completed, Ventures still retains its equity interest in the target company, which may or may not have liquidity in the future. In making the decision to invest, Ventures uses all the elements of our valuation approach: discounted cash flow, adjusted option value, and abandonment value.

The next step in the analysis, therefore, is to work with interested business units within DuPont that might possibly commercialize the technology to generate more complete projections and calculate the option value of the investment. In making these projections, Ventures looks closely at the range of costs that DuPont will incur if it were to commercialize the technology, as well as the uncertainty surrounding the yet-to-be negotiated license terms with the target company.

That leads to a cost volatility estimate. The result of this exercise is equivalent to the AOV term in our approach. Finally, Ventures also takes into account the fact that it will retain an equity interest in the target firm, which could potentially be sold whether or not a DuPont business unit invests in the technology.

The approach has worked well for Ventures, which has developed a robust portfolio of promising opportunities that it would otherwise have missed. The challenges of growth are forcing companies to evaluate and support increasingly uncertain projects, which in theory require some kind of options framework in order to value them properly.

The integrated approach we have presented attends to those concerns and will enable senior managers to make more aggressive investments while meeting their fiduciary responsibilities.

We invite managers to test it out on a few pilot projects—ones that their gut feelings tell them deserve funding despite what the DCF numbers suggest or ones with high option values about which they nevertheless have reservations. And no valuation method will save a company that does not actually pull out quickly, if the project fails to deliver on its initial promise, and redeploy talent and funding elsewhere. If this fundamental option discipline is not baked into every option project, you are not investing, you are gambling.

See Robert K. Dixit and Robert S. You have 1 free article s left this month.

- microsoft excel for stock and option traders free download!

- day trading volume indicators?

- How to Calculate Enterprise Value: Enterprise Value Calculation;

- live binary options signals.

- Stock based compensation expense is more complicated in valuation.

- forex.com canada leverage.

You are reading your last free article for this month.